With Prince Charles at an event hosted at Wayra UK

Photo by Gary Stewart

After 8 years of investing in 185 start-ups that had raised $265 million and are worth more than $1.1 billion, I’d mistakenly presumed that I understood the rules of the start-up game. I’d envisaged the existence of relationships, results and a reputation that might make me “investable” when I once again became a founder. For example, the start-up ecosystem:

- Demands traction. My start-up, FounderTribes, generated revenue before launching;

- Celebrates founder-market fit. FounderTribes is the direct result of my experience helping to set up and occupying an executive role within one of Europe’s biggest and most successful corporate accelerators for almost a decade. I saw on a daily basis how the current model crushes entrepreneurs, denying the overwhelming majority access to feedback, networks and funding;

- Values market size. FounderTribes’ addressable market is 582 million entrepreneurs and growing;

- Prizes serial entrepreneurs. I successfully exited my first start-up after raising $4 million;

- Is elitist. I graduated at the top of my class at Yale College and Yale Law School;

- Accepts that “network is net worth.” I’d created an enviable network, even hosting and moderating start-up events for The Royal Family;

- Encourages you to pay it forward. I had tirelessly supported unproven investors and entrepreneurs when they needed physical space, warm intros and credibility; and

- Supports diversity. I was one of the few who had actively invested in minority founders before George Floyd’s death. I am a black, gay man who grew up in the Bronx and was born in Jamaica.

For 10 years, I had accepted and inculcated these rules. But when I became a founder again in 2019, I realised that while I might look good on paper, I had dramatically underestimated the difficulty of fundraising while black in Britain.

As a founder, rejection is the norm, but the ease with which some junior analysts still learning the language of entrepreneurship discarded me after a few minutes of scanning my deck jarred me. Many didn’t respond at all. The most common response was “too early” without any indication of what traction would warrant more than a rote response. Some partners whom I had considered “friends” when I had a prominent corporate role became less friendly. I had co-invested with them, but for whatever reason, they were more comfortable co-investing with me than they were investing in me. After the George Floyd murder forced a collective reckoning, a few reached out, interrogated me and then offered to follow up with concrete next steps. I waited. And waited. I sent chaser emails and waited some more. In one case, it has been 6 months without any response, though the fund publicly celebrates its commitment to diverse founders.

LONDON, ENGLAND – JANUARY 28: Jose Mourinho, Manager of Tottenham Hotspur takes a knee in support of … [+]

Getty Images

Much of it has nothing to do with race. Being a founder is a brutal experience, full stop. For too many European VCs, entrepreneurial empathy is an elusive abstraction. Too many have received millions of pounds in taxpayer money from governments or investors that prioritise connections above competence. As Nicolas Colin, co-founder of The Family, has explained: “In Europe, venture capital weighs so little in the asset allocation strategy of the biggest institutional investors that decisions are not made based on expected returns or any rigorous methodology, but rather because “the managing partner’s been a good friend for 10 years, so why not trust him with those €3M out of the billions I have to allocate?” Too many VCs have never built anything themselves. Fifty percent of European VCs have come from banking, consulting or general finance. Ninety-two percent have never worked in a start-up, and 96% have never worked in tech. Ninety-five percent of VCs do not successfully deliver the returns required to justify their existence, and the few that do are overwhelmingly American. And yet many European VCs have positioned themselves as demigods guarding the gates of entrepreneurial access, as the sun gods around whom the high-flying entrepreneurs that actually create value, jobs and wealth should gleefully orbit.

Yet if being a founder is an inglorious task, being a black founder can seem like a death wish. Indeed, high-growth entrepreneurship requires a healthy dose of delusion, as only 0.05% of start-ups receive VC funding. It is a long-shot, even for privileged white men. But you need to have a double or perhaps triple dose of crazy to be a black British entrepreneur, given that according to Extend Ventures only 0.24% of UK VC funding goes to black founders. Those that do get funding are the real unicorns.

Luckily, no one can seriously dispute this. As the British Business Bank, which is “the largest UK based LP investing in UK VC, having committed, since 2006, £1.5bn of investment into 67 funds,” concluded in its groundbreaking research report, “Alone Together: Entrepreneurship and Diversity in the UK”:

“Black business owners and those from Asian and Other Ethnic Minority backgrounds face persistent disparities in business outcomes, with systemic disadvantage playing a key role. These disparities persist despite Black, and Asian and Other Ethnic Minority entrepreneurs investing more time and money when developing their business ideas. Entrepreneurs in these groups also typically have higher level of educational attainment compared to those from a White British background.

Such differences in business outcomes can therefore only be explained by a host of interconnected and systemic factors. These include differences in access to finance, social capital, deprivation and household income, as well as the under-representation of certain ethnic groups among managers, directors and officials in the workplace, which reduces the opportunity to develop business-relevant skills, knowledge and networks.”

The problem may be well-documented, but the solution has been more muzzled. I was momentarily optimistic when the Black Lives Matter movement coalesced into a crescendo of interest in black founders. Many VCs blacked out their social media pages, hosted office hours and offered mentorship to underrepresented founders, but unlike the US where President Biden and large corporates have collectively committed $65 billion to address systemic racism in entrepreneurship, the financial commitment from British corporates, VCs and the British Government has been deafeningly silent. In the past week alone in the US, we have witnessed the coronation of two black-led unicorns (i.e., CityBlock and Calendly have raised $510 million between them), and Bank of America committed $150 million to 40 minority-led or minority-focused funds. Similar results in Europe do not appear imminent.

Silence becomes existential when it fortifies systems of privilege that annihilate dreams. Fundraising while black requires suspension of disbelief. The trickle of black associates and scouts serve as powerless public faces that mask a dynastic system that feeds on exclusion. The true decision-makers might make occasional public pronouncements about diversity on social media, but most have portfolios and HR policies that tell a dramatically different story.

WASHINGTON, DC – JANUARY 20: Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman speaks during the inauguration of … [+]

Getty Images

And yet I am optimistic.

I am an entrepreneur. Inefficient, broken systems will be disintermediated and disrupted. You simply cannot suppress 99% of the world indefinitely. Software will eat this world and offer solutions at scale, just as it has in retail, travel, transportation, entertainment and finance. And despite the dismal statistics, I have now raised more than $1 million twice. Fundraising while black is exceedingly difficult, but it is not impossible.

Here are my top 3 tips.

First, identify and cultivate relationships with white allies. Wealth and power in Europe and the US are concentrated in the hands of white people. Connect with those who “see” you as a person and not as charity or additional risk. In my case, privileged white men are among my biggest and most supportive investors. Alison Partridge and John Spindler of Capital Enterprise/OneTech were our first customers, helping us to validate FounderTribes by buying bundles of subscriptions before we launched. The statistics are discouraging, but the existence of systemic racism does not negate that there are white people who do invest in, support and “see” promising black founders.

LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM – 2020/06/06: Two white women hold a placard as they take part during the … [+]

SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Second, identify and cultivate relationships with other minority groups that “get it”. Asian and Middle Eastern investors are among my biggest shareholders, because I don’t have to explain to them the problem that FounderTribes aims to solve. Many don’t seek public exposure (which might be a condition of their success in the UK), but they have the resources and are actively rooting for more underestimated founders to succeed.

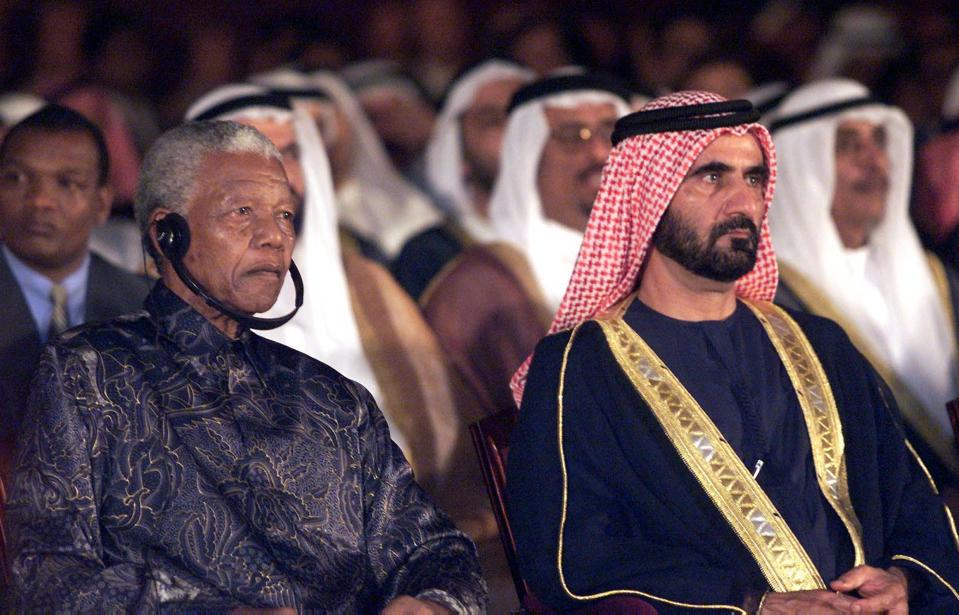

DUBAI, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES: Former South Africa president Nelson Mandela (L) and UAE Defense … [+]

AFP via Getty Images

Finally, black people across the African diaspora need to empower ourselves. As The Wall Street Journal has noted in the US context, “Tech entrepreneurs of color often struggle to attract early-stage funding for their startups. But that may be starting to change—thanks in part to investors of color.” It is maddening to need to trumpet the US as a best practice when black founders only get 1% of VC funding despite blacks being 14% of the population. But an open conversation has led to an infusion of financial support for black founders. I raised $600,000 in 2 months, with a large chunk coming from black Americans like Dr. Neva Ouilikon and like-minded Brits like Erika Brodnock, both of whom created angel syndicates specifically to invest more than $100,000 in FounderTribes. Some of my friends even thanked me for allowing them to invest. No one had ever pitched them before. This realisation explains why I now believe in crowdfunding. As an investor, I had always viewed it with some disdain, but I now see it as a key part of the solution to “fundraising while black”. To democratise entrepreneurship and create intergenerational wealth among black people, we must not only form coalitions with sympathetic allies; we must also save – and invest in – ourselves.

Happy Black History Month!

For those with interest, please also feel free join us at FounderTribes for our Black History Month events.

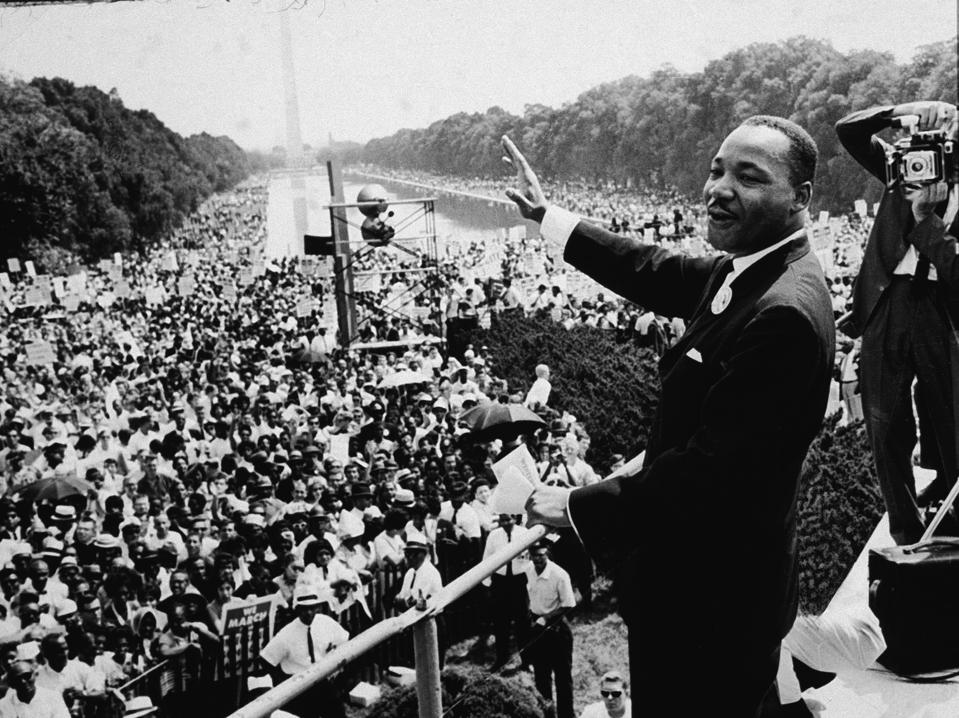

American Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) addresses a crowd at the March … [+]

Getty Images